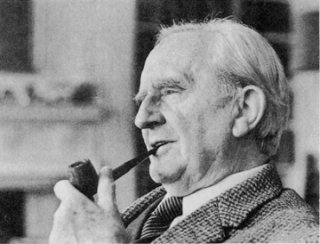

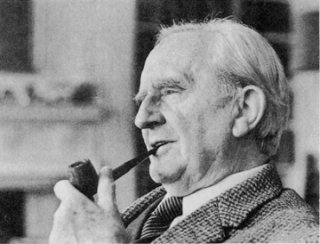

J. R. R. Tolkien

Infobox Writer

name = J. R. R. Tolkien

birthname = John Ronald Reuel Tolkien

imagesize =225px

caption = Tolkien in 1972

birthdate = birth date|1892|1|3|df=y

birthplace = Bloemfontein, Orange Free State

deathdate = 2 September 1973 (aged 81)

deathplace = Bournemouth, England

occupation = Author,

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, CBE (pron-en|ˈtɒlkiːn [See J. R. R. Tolkien's own phonetic transcription published on the illustration in "The Return of the Shadow: The History of The Lord of the Rings, Part One." [Edited by] Christopher Tolkien. London: Unwin Hyman, [25 August] 1988. (The History of Middle-earth; 6) ISBN 0-04-440162-0. The position of the stress is not entirely fixed: stress on the second syllable "(tolsc|kien" rather than "sc|tolkien)" has been used by some members of the Tolkien family.] ) (3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer, poet, philologist, and university professor, best known as the author of the high fantasy classic works "The Hobbit" and "The Lord of the Rings".

Tolkien was Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford from 1925 to 1945, and Merton Professor of English Language and Literature. [Humphrey Carpenter, "Tolkien; The Authorised Biography," page 111, 200.] from 1945 to 1959. He was a close friend of C. S. Lewis – they were both members of the informal literary discussion group known as the Inklings. Tolkien was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II on 28 March 1972.

After his death, Tolkien's son, Christopher, published a series of works based on his father's extensive notes and unpublished manuscripts, including "The Silmarillion". These, together with "The Hobbit" and "The Lord of the Rings", form a connected body of tales, poems, fictional histories, invented languages, and literary essays about an imagined world called Arda, and Middle-earth [Middle-earth" is derived from an Anglicized form of Old Norse Miðgarðr, the land inhabited by humans in Norse mythology] within it. Between 1951 and 1955 Tolkien applied the word "legendarium" to the larger part of these writings. ["Letters", nos. 131, 153, 154, 163.]

While many other authors had published works of fantasy before Tolkien,[cite book |last= de Camp|first= L. Sprague|authorlink= L. Sprague de Camp|title= |year= 1976|publisher= Arkham House |isbn= 0-87054-076-9 The author emphasizes the impact of not only Tolkien but also of William Morris, George MacDonald, Robert E. Howard and E. R. Eddison.] the great success of "The Hobbit" and "The Lord of the Rings" when they were published in paperback in the United States led directly to a popular resurgence of the genre. This has caused Tolkien to be popularly identified as the "father" of modern fantasy literature [cite web|url= http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=8119893978710705002 |title=J. R. R. Tolkien: Father of Modern Fantasy Literature|accessdate = 2006-07-20|author=Mitchell, Christopher|format=Google Video|work="Let There Be Light" series|publisher= [http://www.uctv.tv/ University of California Television] .] —or more precisely, high fantasy.][cite book| last = Clute, John and Grant, John, ed.| year = 1999| title = The Encyclopedia of Fantasy| publisher = St. Martin's Press| id = ISBN 0-312-19869-8] Tolkien's writings have inspired many other works of fantasy and have had a lasting effect on the entire field. In 2008, "The Times" ranked him sixth on a list of 'The 50 greatest British writers since 1945'. [(5 January 2008). [http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/books/article3127837.ece The 50 greatest British writers since 1945] . "The Times". Retrieved on 2008-04-17.] ]

Biography

Tolkien family origins

Most of Tolkien's paternal ancestors were craftsmen. The Tolkien family had its roots in the German Kingdom of Saxony, but had been living in England since the 18th century, becoming "quickly and intensely English". ["Letters", no. 165.] The surname "Tolkien" is Anglicized from "Tollkiehn" (i.e. German "tollkühn", "foolhardy", etymologically corresponding to English "dull-keen", literally "oxymoron"), and the surname "Rashbold", given to two characters in Tolkien's "The Notion Club Papers", is a pun on this. [(undergraduate John Jethro Rashbold, and "old Professor Rashbold at Pembroke"; ME-ref|SD|page 151; "Letters", no. 165.]

Tolkien's maternal grandparents, John and Edith Jane Suffield, were Baptists who lived in Birmingham and owned a shop in the city centre. The Suffield family had run various businesses out of the same building, called Lamb House, since the early 1800s. Beginning in 1812 Tolkien's great-great grandfather William Suffield owned and operated a book and stationery shop there; Tolkien's great-grandfather, also John Suffield, was there from 1826 with a drapery and hosiery business. [ [http://www.birmingham.gov.uk/GenerateContent?CONTENT_ITEM_ID=46417&CONTENT_ITEM_TYPE=0&MENU_ID=13150 Image of John Suffield's shop before demolition with caption] - Birmingham.gov.uk]

Childhood

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born on 3 January 1892, in Bloemfontein in the Orange Free State (now Free State Province, part of South Africa) to Arthur Reuel Tolkien (1857–1896), an English bank manager, and his wife Mabel, "née" Suffield (1870–1904). The couple had left England when Arthur was promoted to head the Bloemfontein office of the British bank he worked for. Tolkien had one sibling, his younger brother, Hilary Arthur Reuel, who was born on 17 February 1894.["Biography", page 22.] ]As a child, Tolkien was bitten by a large baboon spider (a type of tarantula) in the garden, an event which would have later echoes in his stories. ["Biography", page 21.] In another such incident, a family house-boy, who thought Tolkien a beautiful child, took the baby to his kraal to show him off, returning him the next morning. ["Biography, page 13]

When he was three, Tolkien went to England with his mother and brother on what was intended to be a lengthy family visit. His father, however, died in South Africa of rheumatic fever before he could join them. ["Biography", page 24.] This left the family without an income, so Tolkien's mother took him to live with her parents in Stirling Road, Birmingham. Soon after, in 1896, they moved to Sarehole (now in Hall Green), then a Worcestershire village, later annexed to Birmingham. ["Biography", page 27.] He enjoyed exploring Sarehole Mill and Moseley Bog and the Clent Hills and Malvern Hills, which would later inspire scenes in his books, along with other Worcestershire towns and villages such as Bromsgrove, Alcester, and Alvechurch and places such as his aunt's farm of Bag End, the name of which would be used in his fiction. ["Biography", page 113.]

Mabel tutored her two sons, and Ronald, as he was known in the family, was a keen pupil. ["Biography", page 29.] She taught him a great deal of botany, and awakened in her son the enjoyment of the look and feel of plants. Young Tolkien liked to draw landscapes and trees, but his favourite lessons were those concerning languages, and his mother taught him the rudiments of Latin very early.[cite web|last=Doughan|first=David|year=2002|url=http://www.tolkiensociety.org/tolkien/biography.html|title=JRR Tolkien Biography|work=Life of Tolkien|accessdate=2006-03-12] He could read by the age of four, and could write fluently soon afterwards. His mother allowed him to read many books. He disliked "Treasure Island" and "The Pied Piper", and thought "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland" by Lewis Carroll was amusing but disturbing. He liked stories about "Red Indians" and the fantasy works by George MacDonald.][ In addition, the "Fairy Books" of Andrew Lang were particularly important to him and their influence is apparent in some of his later writings. ["Biography", page 30.] ]Tolkien attended King Edward's School, Birmingham and, while a student there, helped "line the route" for the coronation parade of King George V, being posted just outside the gates of Buckingham Palace.["Letters", no. 306.] He later attended St. Philip's School.]Mabel Tolkien was received into the Roman Catholic Church in 1900 despite vehement protests by her Baptist family, ["Biography", page 31.] who then stopped all financial assistance to her. She died of acute complications of diabetes in 1904, when Tolkien was 12, at Fern Cottage in Rednal, which they were then renting. Mabel Tolkien was then about 34 years of age, about as long as a person with diabetes mellitus type 1 could live with no treatment—insulin would not be discovered until two decades later. For the rest of his own life Tolkien felt that his mother had become a martyr for her faith. This feeling had a profound effect on his own Catholic beliefs. ["Biography", page 39.]

Prior to her death, Mabel Tolkien had assigned the guardianship of her sons to Fr. Francis Xavier Morgan of the Birmingham Oratory, who was assigned to bring them up as good Catholics. Tolkien grew up in the Edgbaston area of Birmingham. He lived there in the shadow of Perrott's Folly and the Victorian tower of Edgbaston Waterworks, which may have influenced the images of the dark towers within his works. Another strong influence was the romantic medievalist paintings of Edward Burne-Jones and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood; the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery has a large and world-renowned collection of works and had put it on free public display from around 1908.

Youth

In 1911, while they were at King Edward's School, Birmingham, Tolkien and three friends, Rob Gilson, Geoffrey Smith and Christopher Wiseman, formed a semi-secret society which they called "the T.C.B.S.", the initials standing for "Tea Club and Barrovian Society", alluding to their fondness for drinking tea in Barrow's Stores near the school and, illicitly, in the school library. ["Biography", pages 53–54.] After leaving school, the members stayed in touch, and in December 1914, they held a "Council" in London, at Wiseman's home. For Tolkien, the result of this meeting was a strong dedication to writing poetry.

In the summer of 1911, Tolkien went on holiday in Switzerland, a trip that he recollects vividly in a 1968 letter,[ noting that Bilbo's journey across the Misty Mountains ("including the glissade down the slithering stones into the pine woods") is directly based on his adventures as their party of 12 hiked from Interlaken to Lauterbrunnen, and on to camp in the moraines beyond Mürren. Fifty-seven years later, Tolkien remembered his regret at leaving the view of the eternal snows of Jungfrau and Silberhorn ("the Silvertine (Celebdil) of my dreams"). They went across the Kleine Scheidegg on to Grindelwald and across the Grosse Scheidegg to Meiringen. They continued across the Grimsel Pass and through the upper Valais to Brig, and on to the Aletsch glacier and Zermatt. [ [http://maps.google.de/maps/ms?ie=UTF8&hl=de&om=1&msa=0&msid=108471754903242205397.00000112a38e113bc84bd&ll=46.363988,8.055725&spn=0.843415,1.683655&t=k&z=9 map of the trail of the 1911 expedition] (Google Maps)] ]In October of the same year, Tolkien began studying at Exeter College, one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford. He initially studied Classics but changed to English Language, graduating in 1915.

Courtship and marriage

At the age of 16, Tolkien met Edith Mary Bratt, who was three years older, when J.R.R. and Hilary Tolkien moved into the same boarding house. According to Humphrey Carpenter:His guardian, Father Francis Morgan, viewing Edith as a distraction from Tolkien's school work and horrified that his young charge was seriously involved with a Protestant girl, prohibited him from meeting, talking, or even corresponding with her until he was twenty-one. He obeyed this prohibition to the letter, [cite web| last=Doughan|first=David| year=2002|url= http://www.tolkiensociety.org/tolkien/biography.html#2 | title=War, Lost Tales And Academia|work = J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biographical Sketch|accessdate = 2006-03-12] with one notable early exception which made Father Morgan threaten to cut short his University career if he did not stop. [Humphrey Carpenter: , George Allen & Unwin, 1977, page 43.]

On the evening of his twenty-first birthday, Tolkien wrote to Edith a declaration of his love and asked her to marry him. Edith replied saying that she had already agreed to marry another man, but that she had done so because she had believed Tolkien had forgotten her. The two met up and beneath a railway viaduct renewed their love; Edith returned her engagement ring and announced that she was marrying Tolkien instead. ["Biography", pp. 67–69.] Following their engagement Edith converted to Catholicism at Tolkien's insistence. ["Biography", page 73.] They were formally engaged in Birmingham, in January 1913, and married in Warwick, England, at Saint Mary Immaculate Catholic Church on 22 March 1916. ["Biography", page 86.]

World War I

The United Kingdom was then engaged in fighting World War I, and Tolkien volunteered for military service and was commissioned in the British Army as a Second Lieutenant in the Lancashire Fusiliers. ["Biography", page 85.] He trained with the 13th (Reserve) Battalion on Cannock Chase, Staffordshire, for eleven months. He was then transferred to the 11th (Service) Battalion with the British Expeditionary Force, arriving in France on 4 June 1916. [Garth, John "Tolkien and the Great War", Boston, Houghton Mifflin 2003, pp.89, 138, 147.] He later wrote:Tolkien served as a signals officer during the Battle of the Somme, participating in the Battle of Thiepval Ridge. He came down with trench fever, a disease carried by the lice which were so very plentiful in No Man's Land, on 27 October 1916. According to the memoirs of the Reverend Mervyn S. Evers, Anglican chaplain to the Lancashire Fusilliers:Tolkien was invalided to England on 8 November 1916. ["Biography", page 93.] Many of his dearest friends, including Gilson and Smith of the T.C.B.S., were killed in the war. In later years, Tolkien indignantly declared that those who searched his works for parallels to the Second World War were entirely mistaken:The weak and emaciated Tolkien spent the remainder of the war alternating between hospitals and garrison duties, being deemed medically unfit for general service. [Garth, John "Tolkien and the Great War", Boston, Houghton Mifflin 2003, pp. 207 "et seq."] [ Tolkien's Webley .455 service revolver was put on display in 2006 as part of a Battle of the Somme exhibition in the Imperial War Museum, London.( [http://www.iwm.org.uk/server/show/nav.00o00200h Online exhibit with history and pictures] , [http://www.iwm.org.uk/server/show/ConWebDoc.4097 Press release detailing exhibit] ) and several of his service records, mostly dealing with his health problems, can be seen at the National Archives. [http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/firstworldwar/people/tolkien.htm Online images and transcripts] ] It was at this time Edith bore their first son, John Francis Reuel Tolkien.

Homefront

During his recovery in a cottage in Great Haywood, Staffordshire, England, he began to work on what he called "The Book of Lost Tales", beginning with "The Fall of Gondolin". Throughout 1917 and 1918 his illness kept recurring, but he had recovered enough to do home service at various camps, and was promoted to lieutenant.

When he was stationed at Kingston upon Hull, he and Edith went walking in the woods at nearby Roos, and Edith began to dance for him in a clearing among the flowering hemlock:This incident inspired the account of the meeting of Beren and Lúthien, and Tolkien often referred to Edith as "my Lúthien." [cite web|last=Cater|first=Bill|date=12 April 2001|url= http://www.telegraph.co.uk/arts/main.jhtml?xml=/arts/2001/12/04/batolk04.xml |title=We talked of love, death, and fairy tales|work =UK Telegraph|accessdate = 2006-03-13]

Academic and writing career

Tolkien's first civilian job after World War I was at the "Oxford English Dictionary", where he worked mainly on the history and etymology of words of Germanic origin beginning with the letter "W". [cite book|last= Gilliver| first=Peter|co-authors=Jeremy Marshall and Edmund Weiner|title=The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the OED|publisher=OUP| year=2006] In 1920 he took up a post as Reader in English language at the University of Leeds, and in 1924 was made a professor there. While at Leeds he produced "A Middle English Vocabulary" and, (with E. V. Gordon), a definitive edition of "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight", both becoming academic standard works for many decades. In 1925 he returned to Oxford as Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon, with a fellowship at Pembroke College. During his time at Pembroke, Tolkien wrote "The Hobbit" and the first two volumes of "The Lord of the Rings", largely at 20 Northmoor Road in North Oxford, where a blue plaque was placed in 2002. He also published a philological essay in 1932 on the name 'Nodens', following Sir Mortimer Wheeler's unearthing of a Roman Asclepieion at Lydney Park, Gloucestershire, in 1928. [See "The Name Nodens" (1932) in the bibliographical listing. For the etymology, see Nodens#Etymology.]

Of Tolkien's academic publications, the 1936 lecture "" had a lasting influence on Beowulf research. ["Biography", page 143.] Lewis E. Nicholson said that the article Tolkien wrote about Beowulf is "widely recognized as a turning point in Beowulfian criticism", noting that Tolkien established the primacy of the poetic nature of the work as opposed to the purely linguistic elements. [cite web|last= Ramey|first=Bill| date= 30 March 1998|url= http://ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/billramey/beowulf.htm |title=The Unity of Beowulf: Tolkien and the Critics|work = Wisdom's Children|accessdate = 2006-03-13] At the time, the consensus of scholarship deprecated "Beowulf" for dealing with childish battles with monsters rather than realistic tribal warfare; Tolkien argued that the author of "Beowulf" was addressing human destiny in general, not as limited by particular tribal politics, and therefore the monsters were essential to the poem. [Tolkien: "Finn and Hengest". Chiefly, p.4 in the Introduction by Alan Bliss] Where "Beowulf" does deal with specific tribal struggles, as at Finnsburg, Tolkien argued firmly against reading in fantastic elements. [Tolkien: "Finn and Hengest", the discussion of "Eotena", "passim".] In the essay, Tolkien also revealed how highly he regarded Beowulf: "Beowulf is among my most valued sources," and this influence can be seen in "The Lord of the Rings". [cite web| last=Kennedy|first=Michael|year=2001|url= http://www.triode.net.au/~dragon/tilkal/issue1/beowulf.html |title=Tolkien and Beowulf - Warriors of Middle-earth|work=Amon Hen|accessdate = 2006-05-18]

In 1945, Tolkien moved to Merton College, Oxford, becoming the Merton Professor of English Language and Literature, in which post he remained until his retirement in 1959. Tolkien completed "The Lord of the Rings" in 1948, close to a decade after the first sketches.

Tolkien also helped to translate the "Jerusalem Bible", which was published in 1966. [Rogerson, John. "The Oxford Illustrated History of the Bible", 2001.]

Family

The Tolkiens had four children: John Francis Reuel Tolkien (17 November 1917 – 22 January 2003), Michael Hilary Reuel Tolkien (22 October 1920 – 27 February 1984), Christopher John Reuel Tolkien (born 21 November 1924) and Priscilla Mary Anne Reuel Tolkien (born 18 June 1929). Tolkien was very devoted to his children and sent them illustrated letters from Father Christmas when they were young. There were more characters added each year, such as the Polar Bear, Father Christmas' helper, the Snow Man, the gardener, Ilbereth the elf, his secretary, and various other minor characters. The major characters would relate tales of Father Christmas' battles against goblins who rode on bats and the various pranks committed by the Polar Bear.

Friendships

C.S. Lewis

C. S. Lewis, whom Tolkien first met at Oxford, was perhaps his closest friend and colleague, although their relationship cooled later in their lives. They had a shared affection for good talk, laughter and beer, and in May 1927 Tolkien enrolled Lewis in the Coalbiters club, which read Icelandic sagas in the original Old Norse, and, as Carpenter notes, 'a long and complex friendship had begun.' It was Tolkien (and Hugh Dyson) who helped C.S. Lewis return to Christianity, and Tolkien was accustomed to read aloud passages from "The Silmarillion", "The Hobbit" and "The Lord of the Rings" to Lewis' strong approval and encouragement at the Inklings—often meeting in Lewis' big Magdalen sitting-room—and in private.

It was the arrival of Charles Williams, who worked for the Oxford University Press, that changed the relationship between Tolkien and Lewis. Lewis' enthusiasm shifted almost imperceptibly from Tolkien to Williams, especially during the writing of Lewis' third novel "That Hideous Strength".

Tolkien had for a long time been extremely bothered by what he perceived as Lewis's Anti-Catholicism. In a letter to his son Christopher, he declared:

Lewis' growing reputation as a Christian apologist and his return to the Anglican fold also annoyed Tolkien, who had a deep resentment of the Church of England. By the mid-forties, Tolkien felt that Lewis was receiving a good deal "too much publicity for his or any of our tastes". ["JRR Tolkien, A Biography", HarperCollins Publishers, 1992, p.155]

Tolkien and Lewis might have grown closer during their days at Headington, but this was prevented by Lewis' marriage to Joy Davidman. Tolkien felt that Lewis expected his friends to pay court to her, even though as a bachelor in the thirties, he had often ignored the fact that his friends had wives to go home to. Tolkien also may have felt jealous about a woman's intrusion into their close friendship, just as Edith Tolkien had felt jealous of Lewis' intrusion into her marriage.Fact|date=May 2008 It did not help matters that Lewis did not initially tell Tolkien about his marriage to Davidman or that when Tolkien finally did find out, he also discovered that Lewis had married a divorcee, which was offensive to Tolkien's Catholic beliefs. Tolkien described the marriage as "very strange". [Humphrey Carpenter: "The Inklings", Unwin Paperbacks, 1981, p. 242.]

The cessation of Tolkien's frequent meetings with Lewis in the 1950s marked the end of the 'clubbable' chapter in Tolkien's life, which started with the T.C.B.S. at school and ended with the Inklings at Oxford.

His friendship with Lewis was nevertheless renewed to some degree in later years. As Tolkien was to comment in a letter to Priscilla after Lewis' death in November, 1963:

W.H. Auden

W. H. Auden, who attended Tolkien's lectures as an undergraduate, was also an occasional correspondent and was on friendly terms with Tolkien from the mid-1950s until Tolkien's death, initiated by Auden's fascination with "The Lord of the Rings": Auden was among the most prominent early critics to praise the work. Tolkien wrote in a 1971 letter:

Retirement and old age

During his life in retirement, from 1959 up to his death in 1973, Tolkien received steadily increasing public attention and literary fame. The sale of his books was so profitable that he regretted he had not chosen early retirement.[ While at first he wrote enthusiastic answers to readers' enquiries, he became more and more suspicious of emerging Tolkien fandom, especially among the hippie movement in the United States. [cite web|last=Meras|first=Phyllis|date=15 January 1967|url= http://www.nytimes.com/books/01/02/11/specials/tolkien-gandalf.html |title="Go, Go, Gandalf"|work = New York Times|accessdate = 2006-03-12] In a 1972 letter he deplores having become a cult-figure, but admits that:Fan attention became so intense that Tolkien had to take his phone number out of the public directory ["Letters", no. 332.] and eventually he and Edith moved to Bournemouth on the south coast. ]Tolkien was appointed by Queen Elizabeth II a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the New Year's Honours List of 1 January 1972 [LondonGazette |issue=45554 |date=1 January 1972 |startpage=9 |endpage= |supp=yes |accessdate=2008-07-31] and received the insignia of the Order at Buckingham Palace on 28 March 1972.

Death

Edith Tolkien died on 29 November 1971, at the age of 82. [cite news |first= |last= |authorlink= |coauthors= |title=J. R. R. Tolkien Dead at 81. Wrote 'Lord of the Rings'. Creator of Escapist Literature. Served in World War I. Took 14 Years to Write. |url=http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F30D16FB3A59137A93C1A91782D85F478785F9 |quote=J. R. R. Tolkien, linguist, scholar and author of "The Lord of the Rings," died today in Bournemouth. He was 81 years old. Three sons and a daughter survive. |publisher=New York Times |date=3 September 1973, Monday |accessdate=2007-09-25 ] Tolkien had the name Lúthien engraved on the stone at Wolvercote Cemetery, Oxford. When Tolkien died 21 months later on 2 September 1973, at the age of 81, he was buried in the same grave, with Beren added to his name. The engravings read:

Views

Tolkien was a devout Roman Catholic, and in his religious and political views he was mostly conservative, in the sense of favouring established conventions and orthodoxies over innovation and modernization; in 1943 he wrote, "My political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy (philosophically understood to mean abolition of control, not whiskered men with bombs)—or to 'unconstitutional' Monarchy." ["The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien", no. 52, to Christopher Tolkien on 29 November 1943]

Tolkien had an intense dislike for the side effects of industrialization, which he considered to be devouring the English countryside. For most of his adult life, he was disdainful of automobiles, preferring to ride a bicycle. ["Letters", no. 64, 131, etc.] This attitude can be seen in his work, most famously in the portrayal of the forced "industrialization" of The Shire in "The Lord of the Rings". [cite video | title = J. R. R. Tolkien – Creator Of Middle Earth | publisher = New Line Cinema | format = DVD | year = 2002]

Many [ME-ref|fotr|Foreword] have commented on a number of potential parallels between the Middle-earth saga and events in Tolkien's lifetime. "The Lord of the Rings" is often thought to represent England during and immediately after World War II. Tolkien ardently rejected this opinion in the foreword to the second edition of the novel, stating he preferred applicability to allegory.][ This theme is taken up in greater length in his essay "On Fairy-Stories", where he argues fairy-stories are so apt because they are consistent with themselves and some truths about reality. He concludes that Christianity itself follows this pattern of inner consistency and external truth. His belief in the fundamental truths of Christianity and their place in mythology leads commentators to find Christian themes in "The Lord of the Rings", despite its noticeable lack of overt religious references, religious ceremony or appeals to God. This is not surprising, since the phenomena which in our real world give rise to religious impulses are, in Middle-earth, an ordinary and expected part of the natural world. Use of religious references was frequently a subject of disagreement between Tolkien and C.S. Lewis,Fact|date=March 2008 whose work is often overtly allegorical. This having been said, Tolkien, on many occasions, spoke of the Catholicity or overt Catholic nature of his work. [Pearce, Joseph. "Why Tolkien Says The Lord of the Rings Is Catholic." National Catholic Register (January 12-19, 2003).] [http://www.catholiceducation.org/articles/arts/al0161.html] ]His love of myths and devout faith came together in his assertion that he believed that mythology is the divine echo of "the Truth". [ [http://www.leaderu.com/humanities/wood-biography.html Wood, Ralph C., Biography of J. R. R. Tolkien] .] This view was expressed in his poem "Mythopoeia", ["Tolkien, Mythopoiea (the poem), circa 1931.] and his idea that myths held "fundamental truths" became a central theme of the Inklings in general.

Religion

Tolkien's devout faith was a significant factor in the conversion of C. S. Lewis from atheism to Christianity, although Tolkien was greatly disappointed that Lewis chose to join the Church of England,[cite book|last=Carpenter|first=Humphrey|year=1978|title=The Inklings|publisher=Allen & Unwin Lewis was brought up in the Church of Ireland] which Tolkien objected to as "a pathetic and shadowing medley of half remembered traditions and mutilated beliefs", instead of the Roman Catholic Church. ]In the last years of his life, Tolkien became greatly disappointed by the reforms and changes implemented after the Second Vatican Council, as his grandson Simon Tolkien recalls:

I vividly remember going to church with him in Bournemouth. He was a devout Roman Catholic and it was soon after the Church had changed the liturgy from Latin to English. My grandfather obviously didn't agree with this and made all the responses very loudly in Latin while the rest of the congregation answered in English. I found the whole experience quite excruciating, but my grandfather was oblivious. He simply had to do what he believed to be right. [ [http://www.simontolkien.com/jrrtolkien.html Simon Tolkien - My Grandfather ] ]

According to a recent article:Politics

Tolkien's views were guided by his strict Catholicism. He voiced support for Francisco Franco's regime during the Spanish Civil War upon learning that Republican death squads were destroying churches and killing large numbers of priests and nuns.["Biography", page ?] ["Letters", no. ?] He also expressed admiration for the South African poet and fellow Catholic Roy Campbell after a 1944 meeting. Since Campbell had allegedly served with Franco's armies in Spain, Tolkien regarded him as a defender of the Catholic faith, while C. S. Lewis composed poetry openly satirising Campbell's "mixture of Catholicism and Fascism". ["Letters", no. 83.] ]The question of racist or racialist elements in Tolkien's views and works has been the matter of some scholarly debate. [ [http://tolkien.slimy.com/faq/External.html#Racist Was Tolkien a racist? Were his works?] from the Tolkien Meta-FAQ by Steuard Jensen. Last retrieved 2006-11-16] Christine Chism ["J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia" (2006), s.v. "Racism, Charge of", p. 557.] distinguishes accusations as falling into three categories: intentional racism, [John Yatt, The Guardian (December 2, 2002) writes: "White men are good, 'dark' men are bad, orcs are worst of all." (Other critics such as Tom Shippey and Michael Drout disagree with such clear-cut generalizations of Tolkien's 'white' and 'dark' men into good and bad.) Tolkien's works have also been embraced by self-admitted racists such as the British National Party.] unconscious Eurocentric bias, and an evolution from latent racism in Tolkien's early work to a conscious rejection of racist tendencies in his late work.

Tolkien is known to have condemned Nazi "race-doctrine" and anti-Semitism as "wholly pernicious and unscientific". ["The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien", no. 29, to Stanley Unwin 25 July 1938: When German publishers enquired whether he was of Aryan origin, he declined to answer, instead stating, "I regret that I appear to have no ancestors of that gifted [Jewish] people." He gave his publishers a choice of two letters to send; these quotations are from the less tactful draft, which was not sent - "Letters" no. 30] He also said of racial segregation in South Africa,

The treatment of colour nearly always horrifies anyone going out from Britain. ["The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien" no. 61, to Christopher 18 April 1944]

In 1968, he objected to a description of Middle-earth as "Nordic", a term he said he disliked due to its association with racialist theories. ["Letters", #294] Tolkien had nothing but contempt for Adolf Hitler, whom he accused of "perverting ... and making for ever accursed, that noble northern spirit" which was so dear to him. ["Letters', no. 45.] However, he could get just as agitated over "lesser evils" that struck nearer home; he denounced anti-German fanaticism in the British war effort during World War II. In 1944, he wrote in a letter to his son Christopher:

He was horrified by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, referring to the Bomb's creators as "these lunatic physicists" and "Babel-builders".["Letters", no. 102.] ]Writing

Beginning with "The Book of Lost Tales", written while recuperating from illnesses contracted during The Battle of the Somme, Tolkien devised several themes that were reused in successive drafts of his "legendarium". The two most prominent stories, the tales of Beren and Lúthien and that of Túrin, were carried forward into long narrative poems (published in "The Lays of Beleriand").

Influences

One of the greatest influences on Tolkien was the Arts and Crafts polymath William Morris. Tolkien wished to imitate Morris's prose and poetry romances, [ME-ref|letters|#1] along with the general style and approach, he took elements such as the Dead Marshes in "The Lord of the Rings" [ME-ref|letters|#226] and Mirkwood. ["The Annotated Hobbit", p183, note 10]

Edward Wyke-Smith's "Marvellous Land of the Snergs", with its 'table-high' title characters, strongly influenced the incidents, themes, and depiction of Bilbo's race in "The Hobbit". [Anderson, "The Annotated Hobbit" (1988), 6-7]

Tolkien also cited H. Rider Haggard's novel "She" in a telephone interview: 'I suppose as a boy "She" interested me as much as anything—like the Greek shard of Amyntas [Amenartas] , which was the kind of machine by which everything got moving.' [cite journal | last = Resnick | first = Henry | year = 1967 | title = An Interview with Tolkien | journal = Niekas | pages = 37–47] A supposed facsimile of this potsherd appeared in Haggard's first edition, and the ancient inscription it bore, once translated, led the English characters to She's ancient kingdom. Critics have compared this device to the Testament of Isildur in "The Lord of the Rings" [cite journal | last = Nelson | first = Dale J. | year = 2006 | title = Haggard's "She": Burke's Sublime in a popular romance | journal = Mythlore | issue = Winter-Spring | url = http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0OON/is_3-4_24/ai_n16418915/pg_1 | accessdate = 2007-12-02] and Tolkien's efforts to produce as an illustration a realistic page from the Book of Mazarbul. [cite book | last = Flieger| first = Verlyn | year = 2005 | title = Interrupted Music: The Making Of Tolkien's Mythology | publisher = Kent State University Press | pages = 150 | isbn 0-87338-814-0 | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=Q6zgmCf_kY4C&pg=PA150&dq=Tolkien+%22Red+Book%22+Haggard&ei=M9JSR8T4LZDgoAK-qdGuCw&sig=BxCnRRog4MZyWQlZME6hq-nE-MQ | accessdate = 2007-12-02] Critics starting with Edwin Muir [cite book | last = Muir | first = Edwin | title = The Truth of Imagination: Some Uncollected Reviews and Essays | publisher = Aberdeen University Press | pages = 121 | ISBN 0-08-036392-X] have found resemblances between Haggard's romances and Tolkien's. [cite book | last = Lobdell | first = Jared C. | year = 2004 | title = The World of the Rings: Language, Religion, and Adventure in Tolkien | publisher = Open Court | pages = 5–6 | isbn 978-0-8126-9569-4] [cite book | last = Rogers | first = William N., II | coauthors = Underwood, Michael R. | year = 2000 | title = J.R.R. Tolkien and His Literary Resonances: Views of Middle-Earth | chapter = Gagool and Gollum: Exemplars of Degeneration in "King Solomon's Mines" and "The Hobbit" | editor = George Clark and Daniel Timmons (eds.) | pages = 121–132 | isbn 0-313-30845-4] [cite web | last = Stoddard | first = William H. | month= July | year= 2003 | title = Galadriel and Ayesha: Tolkienian Inspiration? | publisher = Franson Publications | url = http://www.troynovant.com/Stoddard/Tolkien/Galadriel-and-Ayesha.html | accessdate = 2007-12-02]

Tolkien wrote of being impressed as a boy by S. R. Crockett's historical novel "The Black Douglas" and of basing the Necromancer (Sauron) on its villain, Gilles de Retz. ["Letters", p. 391, quoted by Lobdell, 6.] Incidents in both "The Hobbit" and "Lord of the Rings" are similar in narrative and style to the novel, [Anderson, "The Annotated Hobbit" (1988), 150] and its overall style and imagery have been suggested as an influence on Tolkien. [Lobdell, 6–7.]

Tolkien was much inspired by early Germanic, especially Anglo-Saxon literature, poetry and mythology, which were his chosen and much-loved areas of expertise. These sources of inspiration included Anglo-Saxon literature such as "Beowulf", Norse sagas such as the "Volsunga saga" and the "Hervarar saga", [As described by Christopher Tolkien in "Hervarar Saga ok Heidreks Konung" (Oxford University, Trinity College). B. Litt. thesis. 1953/4. [Year uncertain] , "The Battle of the Goths and the Huns", in: Saga-Book (University College, London, for the Viking Society for Northern Research) 14, part 3 (1955–6) [http://www.tolkiensociety.org/tolkien/bibl4.html] ] the "Poetic Edda", the "Prose Edda", the "Nibelungenlied" and numerous other culturally related works.[cite book|first=David|last=Day|authorlink=David Day (Canadian)|date=1 February 2002|title=Tolkien's Ring|location = New York|publisher=Barnes and Noble|id = ISBN 1-58663-527-1] ]Despite the similarities of his work to the "Volsunga saga" and the "Nibelungenlied", which were the basis for Richard Wagner's opera series,Tolkien dismissed critics' direct comparisons to Wagner, telling his publisher, "Both rings were round, and there the resemblance ceases." However, some critics [ [http://www.wagner-dc.org/haymes04_lec.html The Two Rings ] ] [ [http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Front_Page/EA11Aa02.html Asia Times ] ] [ [http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Front_Page/ID24Aa01.html Asia Times Online :: Asian News, Business and Economy - Tolkien's Christianity and the pagan tragedy ] ] believe that Tolkien was, in fact, indebted to Wagner for elements such as the "concept of the Ring as giving the owner mastery of the world..." [ [http://tolkienonline.de/etep/1ring5.html 5. Tolkien's Ring and Der Ring des Nibelungen ] ] Two of the characteristics possessed by the One Ring, its inherent malevolence and corrupting power upon minds and wills, were not present in the mythical sources but have a central role in Wagner's opera.

Tolkien himself also acknowledged Homer, Sophocles, and the Finnish and Karelian "Kalevala" as influences or sources for some of his stories and ideas. [cite web|last=Handwerk|first=Brian|date=1 March 2004|url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2001/12/1219_tolkienroots.html| title=Lord of the Rings Inspired by an Ancient Epic|work = National Geographic News|accessdate = 2006-03-13]

Dimitra Fimi, along with Douglas Anderson, John Garth and many other prominent Tolkien scholars show that Tolkien also drew influence from a variety of Celtic (Scottish , Welsh and Gaelic) history and legends, [Fimi, Dimitra, "'Mad' Elves and 'elusive beauty': some Celtic strands of Tolkien's mythology, "Folklore", Volume 117, Issue 2 August 2006 , pages 156 - 170 [http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m2386/is_2_117/ai_n16676591 http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m2386/is_2_117/ai_n16676591] ] [ [http://muse.jhu.edu/login?uri=/journals/tolkien_studies/v004/4.1fimi.html http://muse.jhu.edu/login?uri=/journals/tolkien_studies/v004/4.1fimi.html] ] though after the "Silmarillion" manuscript was rejected, in part for its 'eye-splitting' Celtic names, Tolkien rejected their Celtic origin:

A major philosophical influence on his writing is Alfred the Great's Anglo-Saxon translation of Boethius' "Consolation of Philosophy", known as the "Lays of Boethius". [cite web|last=Gardner|first=John|date=23 October 1977|url= http://www.nytimes.com/1977/10/23/books/tolkien-silmarillion.html| title=The World of Tolkien|work = New York Times|accessdate = 2006-03-13] Characters in "The Lord of the Rings" such as Frodo, Treebeard, and Elrond make noticeably Boethian remarks. Also, Catholic theology and imagery played a part in fashioning Tolkien's creative imagination, suffused as it was by his deeply religious spirit. [cite web|last=Bofetti|first=Jason|month=November | year=2001|url= http://www.crisismagazine.com/november2001/feature7.htm |title=Tolkien's Catholic Imagination|work = Crisis Magazine|accessdate = 2006-08-30] "The Silmarillion"

Tolkien wrote a brief 'Sketch of the Mythology' of which the tales of Beren and Lúthien and of Túrin were part, and that Sketch eventually evolved into " the Quenta Silmarillion", an epic history that Tolkien started three times but never published. Tolkien hoped to publish it along with "The Lord of the Rings", but publishers (both Allen & Unwin and Collins) got cold feet; moreover printing costs were very high in the post-war years, leading to "The Lord of the Rings" being published in three books. [Hammond, Wayne G. "J.R.R. Tolkien: A Descriptive Bibliography", London: January 1993, Saint Paul's Biographies, ISBN 1-873040-11-3, American edition ISBN 0-938768-42-5] The story of this continuous redrafting is told in the posthumous series "The History of Middle-earth", which was edited by Tolkien's son, Christopher Tolkien. From around 1936, he began to extend this framework to include the tale of "The Fall of Númenor", which was inspired by the legend of Atlantis.

Children's books

In addition to his mythopoetic compositions, Tolkien enjoyed inventing fantasy stories to entertain his children. [cite web|last=Phillip|first=Norman|year=2005|url= http://www.nytimes.com/books/01/02/11/specials/tolkien-mag67.html | title=The Prevalence of Hobbits|work = New York Times|accessdate = 2006-03-12] He wrote annual Christmas letters from Father Christmas for them, building up a series of short stories (later compiled and published as "The Father Christmas Letters"). Other stories included "Mr. Bliss", "Roverandom", "Smith of Wootton Major" and "Farmer Giles of Ham". "Roverandom" and "Smith of Wootton Major", like "The Hobbit", borrowed ideas from his "legendarium".

"The Hobbit"

Tolkien never expected his stories to become popular, but by sheer accident a book he had written some years before for his own children, called "The Hobbit", came in 1936 to the attention of Susan Dagnall, an employee of the London publishing firm George Allen & Unwin, who persuaded him to submit it for publication. [cite web|author =Times Editorial Staff|date=3 September 1973|url= http://www.nytimes.com/books/01/02/11/specials/tolkien-obit.html |title=J.R.R. Tolkien Dead at 81: Wrote "The Lord of the Rings"|work = New York Times|accessdate = 2006-03-12] However, the book attracted adult readers as well, and it became popular enough for the publisher to ask Tolkien to work on a sequel.

"The Lord of the Rings"

Even though he felt uninspired on the topic, this request prompted Tolkien to begin what would become his most famous work: the epic three-volume novel "The Lord of the Rings" (published 1954–55). Tolkien spent more than ten years writing the primary narrative and appendices for "The Lord of the Rings", during which time he received the constant support of the Inklings, in particular his closest friend Lewis, the author of "The Chronicles of Narnia". Both "The Hobbit" and "The Lord of the Rings" are set against the background of "The Silmarillion", but in a time long after it.

Tolkien at first intended "The Lord of the Rings" to be a children's tale in the style of "The Hobbit", but it quickly grew darker and more serious in the writing. [cite web|author =Times Editorial Staff|date=5 June 1955|url=http://www.nytimes.com/books/01/02/11/specials/tolkien-oxford.html| title=Oxford Calling|work = New York Times|accessdate = 2006-03-12] Though a direct sequel to "The Hobbit", it addressed an older audience, drawing on the immense back story of Beleriand that Tolkien had constructed in previous years, and which eventually saw posthumous publication in "The Silmarillion" and other volumes. Tolkien's influence weighs heavily on the fantasy genre that grew up after the success of "The Lord of the Rings".

"The Lord of the Rings" became immensely popular in the 1960s and has remained so ever since, ranking as one of the most popular works of fiction of the 20th century, judged by both sales and reader surveys. [cite web|author= Seiler, Andy |date= 16 December 2003|url=http://www.usatoday.com/life/movies/news/2003-12-12-lotr-main_x.htm| title='Rings' comes full circle|work = USA Today |accessdate = 2006-03-12] In the 2003 "Big Read" survey conducted by the BBC, "The Lord of the Rings" was found to be the "Nation's Best-loved Book". Australians voted "The Lord of the Rings" "My Favourite Book" in a 2004 survey conducted by the Australian ABC. [cite web|author= Cooper, Callista |date= 5 December 2005|url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/newsitems/200512/s1523327.htm| title=Epic trilogy tops favorite film poll|work = ABC News Online|accessdate = 2006-03-12] In a 1999 poll of Amazon.com customers, "The Lord of the Rings" was judged to be their favourite "book of the millennium". [cite web|author= O'Hehir, Andrew |date= 4 June 2001|url= http://www.salon.com/books/feature/2001/06/04/tolkien/ |title=The book of the century|work = Salon.com|accessdate = 2006-03-12] In 2002 Tolkien was voted the 92nd "greatest Briton" in a poll conducted by the BBC, and in 2004 he was voted 35th in the SABC3's Great South Africans, the only person to appear in both lists. His popularity is not limited to the English-speaking world: in a 2004 poll inspired by the UK’s "Big Read" survey, about 250,000 Germans found "The Lord of the Rings" to be their favourite work of literature. [cite web|author =Diver, Krysia|date=5 October 2004|url= http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2004/10/04/1096871805007.html |title=A lord for Germany|work =The Sydney Morning Herald|accessdate = 2006-03-12]

Posthumous publications

Tolkien had appointed his son Christopher to be his literary executor, and he (with assistance from Guy Gavriel Kay, later a well-known fantasy author in his own right) organized some of the unpublished material into a single coherent volume, published as "The Silmarillion" in lty|1977 – his father had previously attempted to get a collection of 'Silmarillion' material published in 1937 before writing "The Lord of the Rings" [see "The History Of Middle-Earth"] .

In lty|1980 Christopher Tolkien followed "The Silmarillion" with a collection of more fragmentary material under the title "Unfinished Tales". In subsequent years (lty|1983–lty|1996) he published a large amount of the remaining unpublished materials together with notes and extensive commentary in a series of twelve volumes called "The History of Middle-earth". They contain unfinished, abandoned, alternative and outright contradictory accounts, since they were always a work in progress, and Tolkien only rarely settled on a definitive version for any of the stories. There is not complete consistency between "The Lord of the Rings" and "The Hobbit", the two most closely related works, because Tolkien never fully integrated all their traditions into each other. He commented in 1965, while editing "The Hobbit" for a third edition, that he would have preferred to completely rewrite the entire book due to the style of its prose. [cite web|last= Martinez |first=Michael|date=7 December 2004|url= http://www.merp.com/essays/MichaelMartinez/michaelmartinezsuite101essay122 |title=Middle-earth Revised, Again|work = Merp.com|accessdate = 2006-03-13]

More recently, in lty|2007, the collection was completed with the publication of "The Children of Húrin" by HarperCollins (in the UK and Canada) and Houghton Mifflin in the USA. The novel tells the story of Túrin Turambar and his sister Nienor, children of Húrin Thalion. The material was compiled by Christopher Tolkien from "The Silmarillion", "Unfinished Tales", "The History of Middle-earth" and unpublished works.

The Department of Special Collections and University Archives of John P. Raynor, S.J., Library at Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin preserves many of Tolkien's manuscripts; [ [http://www.marquette.edu/library/collections/archives/tolkien.html Tolkien Archives] at Raynor Library, Marquette University] other original material is in Oxford University's Bodleian Library. Marquette has the manuscripts and proofs of "The Lord of the Rings", "The Hobbit" and other works, including "Farmer Giles of Ham", while the Bodleian holds the "Silmarillion" papers and Tolkien's academic work. [cite web|author =McDowell, Edwin |date=4 September 1983|url= http://www.nytimes.com/books/01/02/11/specials/tolkien-revisited.html |title=Middle-earth Revisited|work = New York Times|accessdate = 2006-03-12]

Languages and philology

Linguistic career

Both Tolkien's academic career and his literary production are inseparable from his love of language and philology. He specialized in Ancient Greek philology at university, and in 1915 graduated with Old Norse as special subject. He worked for the Oxford English Dictionary from 1918, and is credited with having worked on a number of words starting with the letter W, including walrus, over which he struggled mightily. [Winchester, Simon (2003). "The Meaning of Everything: The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary." Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860702-4; and Gilliver, Peter, Jeremy Marshall and Edmund Weiner (2006). "The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary." Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-861069-6] In 1920, he went to Leeds as Reader in English language, where he claimed credit for raising the number of students of linguistics from five to twenty. He gave courses in Old English heroic verse, history of English, various Old English and Middle English texts, Old and Middle English philology, introductory Germanic philology, Gothic, Old Icelandic, and Medieval Welsh. When in 1925, aged thirty-three, Tolkien applied for the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon, he boasted that his students of Germanic philology in Leeds had even formed a "Viking Club". [(Letter dated 27 June 1925 to the Electors of the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon, University of Oxford, "Letters", no. 7.] He also had a certain, if imperfect, knowledge of Finnish. [Grotta, Daniel (2001) J.R.R. Tolkien Architect of Middle Earth. Running Press Book Publishers. ISBN 0762409568]

Privately, Tolkien was attracted to "things of racial and linguistic significance", and he entertained notions of an inherited taste of language, which he termed the "native tongue" as opposed to "cradle tongue" in his 1955 lecture "English and Welsh", which is crucial to his understanding of race and language. He considered West Midlands dialect of Middle English to be his own "native tongue", and, as he wrote to W. H. Auden in 1955, "I am a West-midlander by blood (and took to early west-midland Middle English as a known tongue as soon as I set eyes on it)". ["Letters", no. 163.]

Language construction

:"See also: Languages of Middle-earth"Parallel to Tolkien's professional work as a philologist, and sometimes overshadowing this work, to the effect that his academic output remained rather thin, was his affection for the construction of artificial languages. The best developed of these are Quenya and Sindarin, the etymological connection between which formed the core of much of Tolkien's "legendarium". Language and grammar for Tolkien was a matter of aesthetics and euphony, and Quenya in particular was designed from "phonaesthetic" considerations; it was intended as an "Elvenlatin", and was phonologically based on Latin, with ingredients from Finnish, Welsh, English, and Greek.["Letters", no. 144.] A notable addition came in late 1945 with Adûnaic or Númenórean, a language of a "faintly Semitic flavour", connected with Tolkien's Atlantis legend, which by "The Notion Club Papers" ties directly into his ideas about inability of language to be inherited, and via the "Second Age" and the story of Eärendil was grounded in the legendarium, thereby providing a link of Tolkien's twentieth-century "real primary world" with the legendary past of his Middle-earth.]Tolkien considered languages inseparable from the mythology associated with them, and he consequently took a dim view of auxiliary languages: in 1930 a congress of Esperantists were told as much by him, in his lecture "A Secret Vice", "Your language construction will breed a mythology", but by 1956 he had concluded that "Volapük, Esperanto, Ido, Novial, &c, &c, are dead, far deader than ancient unused languages, because their authors never invented any Esperanto legends".["Letters", no. 180.] ]The popularity of Tolkien's books has had a small but lasting effect on the use of language in fantasy literature in particular, and even on mainstream dictionaries, which today commonly accept Tolkien's idiosyncratic spellings "dwarves" and "dwarvish" (alongside "dwarfs" and "dwarfish"), which had been little used since the mid-1800s and earlier. (In fact, according to Tolkien, had the Old English plural survived, it would have been "dwerrows".) He also coined the term "eucatastrophe", though it remains mainly used in connection with his own work.

Legacy

Adaptations

In a 1951 letter to Milton Waldman, Tolkien writes about his intentions to create a "body of more or less connected legend", of which

The hands and minds of many artists have indeed been inspired by Tolkien's legends. Personally known to him were Pauline Baynes (Tolkien's favourite illustrator of "The Adventures of Tom Bombadil" and "Farmer Giles of Ham") and Donald Swann (who set the music to "The Road Goes Ever On"). Queen Margrethe II of Denmark created illustrations to "The Lord of the Rings" in the early 1970s. She sent them to Tolkien, who was struck by the similarity they bore in style to his own drawings. [cite web|author= Thygesen, Peter |year= Autumn, 1999|url= http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3760/is_199910/ai_n8868143| title=Queen Margrethe II: Denmark's monarch for a modern age|work = Scandinavian Review|accessdate = 2006-03-12]

However, Tolkien was not fond of all the artistic representation of his works that were produced in his lifetime, and was sometimes harshly disapproving. In 1946, he rejected suggestions for illustrations by Horus Engels for the German edition of "The Hobbit" as "too Disnified",

Tolkien was sceptical of the emerging Tolkien fandom in the United States, and in 1954 he returned proposals for the dust jackets of the American edition of "The Lord of the Rings":

In 1958, after receiving a screenplay for a proposed movie adaptation of "The Lord of the Rings" by Morton Grady Zimmerman, Tolkien wrote:

Tolkien went on to criticize the script scene by scene ("yet one more scene of screams and rather meaningless slashings"). But Tolkien was in principle open to the idea of a movie adaptation. He sold the film, stage and merchandise rights of "The Hobbit" and "The Lord of the Rings" to United Artists in 1968. However, guided by an intense hatred of their past work, Tolkien expressly forbade that The Walt Disney Company should ever become involved in any future productionsME-fact|date=October 2007.

United Artists never made a film, although director John Boorman was planning a live-action film in the early 1970s. In 1976 the rights were sold to Tolkien Enterprises, a division of the Saul Zaentz Company, and the first movie adaptation of "The Lord of the Rings" appeared in 1978, an animated rotoscoping film directed by Ralph Bakshi with screenplay by the fantasy writer Peter S. Beagle. It covered only the first half of the story of "The Lord of the Rings". [cite web|author= Canby, Vincent |date= 15 November 1978|url= http://www.nytimes.com/books/01/02/11/specials/tolkien-lordfilm.html| title= Film: 'The Lord of the Rings' From Ralph Bakshi |work = New York Times|accessdate = 2006-03-12] In 1977 an animated TV production of "The Hobbit" was made by Rankin-Bass, and in 1980 they produced an animated "The Return of the King", which covered some of the portions of "The Lord of the Rings" that Bakshi was unable to complete.

From 2001 to 2003, New Line Cinema released "The Lord of the Rings" as a trilogy of live-action films that were filmed in New Zealand and directed by Peter Jackson. The series was successful, performing well commercially and winning numerous Oscars.

Memorials

Posthumously named after Tolkien are the Tolkien Road in Eastbourne, East Sussex, and the asteroid 2675 Tolkien discovered in 1982. Tolkien Way in Stoke-on-Trent is named after Tolkien's eldest son, Fr. John Francis Tolkien, who was the priest in charge at the nearby Roman Catholic Church of Our Lady of the Angels and St. Peter in Chains. [cite web|title=People of Stoke-on-Trent|url= http://www.thepotteries.org/people/tolkien_john.htm |accessdate = 2005-03-13] There is also a professorship in Tolkien's name at Oxford, the J.R.R. Tolkien Professor of English Literature and Language. [ [http://www.admin.ox.ac.uk/statutes/regulations/185-084.shtml Schedule of Statutory Professorships] in "Statutes and Regulations" of the University of Oxford online at ox.ac.uk/statutes (accessed 27 November 2007)]

Blue plaques

There are six blue plaques that commemorate places associated with Tolkien, one in Oxford, one in Harrogate, and four in Birmingham. The Birmingham plaques commemorate three of his childhood homes right up to the time he left to attend Oxford University. The Oxford plaque commemorates the residence where Tolkien wrote "The Hobbit" and most of "The Lord of the Rings". The Harrogate plaque commemorates the residence where Tolkien convalesced from trench fever.

Bibliography

"Please see Bibliography of J. R. R. Tolkien"

References

General references

* "Biography": cite book

first = Humphrey | last = Carpenter | authorlink = Humphrey Carpenter

year = 1977

title = Tolkien: A Biography

location = New York

publisher = Ballantine Books

id = ISBN 0-04-928037-6

* "Letters": cite book

author = Carpenter, Humphrey and Tolkien, Christopher (eds.)

year = 1981

title = The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien

location = London

publisher = George Allen & Unwin

id = ISBN 0-04-826005-3

Notes

Further reading

A small selection of books about Tolkien and his works:

* cite book

editor = Anderson, Douglas A., Michael D. C. Drout and Verlyn Flieger

year = 2004

title = Tolkien Studies, An Annual Scholarly Review Vol. I

publisher = West Virginia University Press

id = ISBN 0-937058-87-4

* cite book

title = The Inklings: C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, Charles Williams and Their Friends

first = Humphrey | last = Carpenter

year = 1979

id = ISBN 0-395-27628-4

* cite book

year = 2003

title = Tolkien the Medievalist | editor = Chance, Jane

location = London, New York | publisher = Routledge

id = ISBN 0-415-28944-0

* cite book

year = 2004

title = Tolkien and the Invention of Myth, a Reader

editor = Chance, Jane

location = Louisville | publisher = University Press of Kentucky

id = ISBN 0-8131-2301-1

* cite book

title = Defending Middle-earth: Tolkien, Myth and Modernity

first = Patrick | last = Curry | year = 2004

id = ISBN 0-618-47885-X

* cite book

year = 2006

title =

editor = Drout, Michael D. C.

location = New York City | publisher = Routledge

id = ISBN 0-415969425.

* cite book

title = The Inklings Handbook: The Lives, Thought and Writings of C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Charles Williams, Owen Barfield, and Their Friends

first = Colin | last = Duriez | co-authors = David Porter | year = 2001

id = ISBN 1-902694-13-9

* cite book

title = Tolkien and C.S. Lewis: The Gift of Friendship

first = Colin | last = Duriez | year = 2003

id = ISBN 1-58768-026-2

* cite book

year = 2000

title = Tolkien's Legendarium: Essays on The History of Middle-earth

editor = Flieger, Verlyn and Carl F. Hostetter

location = Westport, Conn | publisher = Greenwood Press

id = ISBN 0-313-30530-7. DDC 823.912. LC PR6039.

* cite book

title = The Atlas of Middle-earth

last = Fonstad | first = Karen Wynn

year = 1991 | location = Boston | publisher = Houghton Mifflin

id = ISBN 0-618-126996

* cite book

title = Tolkien and the Great War

last = Garth | first = John | year = 2003

publisher = Harper-Collins

id = ISBN 0-00-711953-4

* cite book

author= Gilliver, Peter; Marshall, Jeremy; Weiner, Edmund

year = 2006

title = The Ring of Words

publisher = Oxford University Press

isbn= 0198610696

*

* cite book

title = Meditations on Middle-earth: New Writing on the Worlds of J. R. R. Tolkien

first = Karen | last = Haber

year = 2001 | publisher = St. Martin's Press

id = ISBN 0-312-27536-6

* cite book

year = 2003

title = Tolkien and Politics | editor = Harrington, Patrick

location = London, England | publisher = Third Way Publications Ltd

id = ISBN 0-9544788-2-7

* cite book

editor = Lee, S. D., and E. Solopova

year = 2005

title = The Keys of Middle-earth: Discovering Medieval Literature through the Fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien

publisher = Palgrave Macmillan

id = ISBN 1-4039-4671-X

* cite book

first = Timothy R | last = O'Neill

year = 1979

title = The Individuated Hobbit: Jung, Tolkien and the Archetypes of Middle-earth

location = Boston | publisher = Houghton Mifflin Company

id =ISBN 0-395-28208-X

* cite book

first = Joseph | last = Pearce

year = 1998

title = Tolkien: Man and Myth

location = London | publisher = HarperCollinsPublishers

id = ISBN 0-00-274018-4

* cite book

first = Michael | last = Perry | year = 2006

title = Untangling Tolkien: A Chronology and Commentary for The Lord of the Rings

location = Seattle | publisher = Inkling Books

id = ISBN 1-58742-019-8

* cite book

year = 2003

title = El Señor de los Anillos | editor = Pytrell, Ariel

location = Buenos Aires, Argentina | publisher = Mondragón Argentina

id = ISBN 987-20607-0-3

* cite book

author= Shippey, Tom

year = 2000

title = J. R. R. Tolkien – Author of the Century

location = Boston, New York | publisher = Houghton Mifflin Company

id =ISBN 0-618-12764-X, ISBN 0-618-25759-4 (pbk)

* cite book

author= Simonson, Martin

year = 2008

title = The Lord of the Rings and the Western Narrative Tradition

location = Zurich, Jena | publisher = Walking Tree Publishers

id =ISBN 978-3-905703-09-2

* cite book

first =Barbara | last = Strachey

year = 1981

title = Journeys of Frodo: an Atlas of The Lord of the Rings

location = London, Boston | publisher = Allen & Unwin

id = ISBN 0-04-912016-6

* cite book

first = John & Priscilla | last = Tolkien

year = 1992

title = The Tolkien Family Album

location = London | publisher = HarperCollins

id = ISBN 0-261-10239-7

* cite book

first = Michael | last = White

year = 2003

title = Tolkien: A Biography

publisher = New American Library

id = ISBN 0-451-21242-8

External links

* [http://www.tolkien.co.uk HarperCollins Tolkien Website]

* [http://www.tolkiensociety.org/tolkien/biography.html Tolkien Biography] (The Tolkien Society)

* [http://www.marquette.edu/library/collections/archives/tolkien.html Tolkien Archives] at the Raynor Library, Marquette University

* [http://www.tolkienlibrary.com/ The Tolkien Library]

* [http://www.tolkienguide.com/ The Tolkien Collector's Guide]

*worldcat id|id=lccn-n79-5673

*IBList |type=author|id=54|name=J.R.R. Tolkien

Persondata

NAME=Tolkien, J. R. R.

ALTERNATIVE NAMES=Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel

SHORT DESCRIPTION=British philologist and author

DATE OF BIRTH=birth date|1892|1|3|df=y

PLACE OF BIRTH=Bloemfontein, Orange Free State

DATE OF DEATH=death date|1973|9|2|df=y

PLACE OF DEATH=Bournemouth, England

Источник: J. R. R. Tolkien