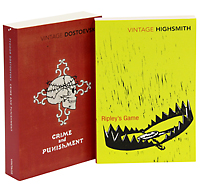

Книга: Fyodor Dostoevsky, Patricia Highsmith «Fyodor Dostoevsky. Crime and Punishment. Patricia Highsmith. Ripley's Game (комплект из 2 книг)»

|

Серия: "Vintage Classics" Содержание:Книга 1, Crime and Punishment, Книга 2, Ripley's Game Издательство: "Vintage" (2007)

ISBN: 978-0-099-51136-6 Купить за 789 руб на Озоне |

Fyodor Dostoevsky

Infobox Writer

name = Fyodor Dostoevsky

birthdate = birth date|1821|10|30|mf=y

birthplace =

deathdate = Death date and age|1881|1|28|1821|11|11

deathplace =

occupation =

nationality =

period=

genre=

subject=

movement=

notableworks= "

"

spouse=

children=

relatives=

influences= Writers:

Philosophers:

influenced =

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky ( _ru. Фёдор Миха́йлович Достое́вский, IPA-ru|ˈfʲodər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪtɕ dəstɐˈjɛfskʲɪj, sometimes transliterated Dostoyevsky, Dostoievsky, Dostojevskij, Dostoevski or Dostoevskii Audio|ru-Dostoevsky.ogg|listen) (OldStyleDate|November 11|1821|October 30 – OldStyleDate|February 9|1881|January 28) was a Russian

Dostoevsky's literary output explores human

Biography

Family origins

Dostoevsky was Russian on his mother's side. His paternal ancestors were from a place called Dostoyeve, natives of the guberniya (province) of

last=Dostoyevsky

first=Aimée

title=FYODOR DOSTOYEVSKY: A STUDY

place=Honolulu, HAWAII

publisher= [http://www.universitypressofthepacific.com/ University Press of the Pacific]

year=2001

url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/61397936

isbn=0898751659

pages=1, 6-7]

Early life

Dostoevsky was the second of seven children born to Mikhail and Maria Dostoevsky. Dostoevsky's father Mikhail was a retired military surgeon and a violent

There are many stories of Dostoevsky's father's despotic treatment of his children. After returning home from work, he would take a nap while his children, ordered to keep absolutely silent, stood by their slumbering father in shifts and swatted at any flies that came near his head. However, it is the opinion of Joseph Frank, a biographer of Dostoevsky, that the father figure in "

Shortly after his mother died of

Dostoevsky had

At the

Beginnings of a literary career

Dostoevsky was made a

In 1846, Belinsky and many others reacted negatively to his novella, "", a psychological study of a bureaucrat whose alter ego overtakes his life. Dostoevsky's fame began to cool. Much of his work after "

Exile in Siberia

Dostoevsky was arrested and imprisoned on

He was released from prison in 1854, and was required to serve in the

Post-prison maturation as writer

Dostoevsky's experiences in prison and the army resulted in major changes in his political and religious convictions. Firstly, his ordeal somehow caused him to become disillusioned with 'Western' ideas; he repudiated the contemporary Western

Dostoevsky now displayed a much more critical stance on contemporary European philosophy and turned with intellectual rigour against the Nihilist and Socialist movements; and much of his post-prison work -- particularly the novel, "The Possessed" and the essays, "The Diary of a Writer" -- contains both criticism of socialist and nihilist ideas, as well as thinly-veiled parodies of contemporary Western-influenced Russian intellectuals (

Dostoevsky's post-prison fiction abandoned the European-style domestic melodramas and quaint character studies of his youthful work in favor of dark, more complex story-lines and situations, played-out by brooding, tortured characters -- often styled partly on Dostoevsky himself -- who agonized over existential themes of spiritual torment, religious awakening, and the psychological confusion caused by the conflict between traditional Russian culture and the influx of modern, Western philosophy. This, nonetheless, does not take from the debt which Dostoevsky owed to the earlier (Western influenced within Russia

Later literary career

In December 1859, Dostoevsky returned to

Dostoevsky was devastated by his wife's death in 1864, which was followed shortly thereafter by his brother's death. He was financially crippled by business debts and the need to provide for his wife's son from her earlier marriage and his brother's widow and children. Dostoevsky sank into a deep depression, frequenting gambling parlors and accumulating massive losses at the tables.

Dostoevsky suffered from an acute gambling compulsion as well as from its consequences. By one account "Crime and Punishment", possibly his best known novel, was completed in a mad hurry because Dostoevsky was in urgent need of an advance from his publisher. He had been left practically penniless after a gambling spree. Dostoevsky wrote "The Gambler" simultaneously in order to satisfy an agreement with his publisher

Dostoevsky is also known to have influenced and been influenced by the philosopher

In 1877, Dostoevsky gave the keynote

In his later years, Fyodor Dostoevsky lived for a long time at the resort of

Works and influence

Dostoevsky's influence has been acclaimed by a wide variety of writers, including

In a book of interviews with Arthur Power ("Conversations with James Joyce"),

In her essay "The Russian Point of View",

Dostoevsky displayed a nuanced understanding of human psychology in his major works. He created an opus of vitality and almost hypnotic power, characterized by feverishly dramatized scenes where his characters are, frequently in scandalous and explosive atmosphere, passionately engaged in

His characters fall into a few distinct categories: humble and self-effacing Christians (

Dostoevsky's novels are compressed in time (many cover only a few days) and this enables the author to get rid of one of the dominant traits of realist prose, the corrosion of human life in the process of the time flux — his characters primarily embody spiritual values, and these are, by definition, timeless. Other obsessive themes include

Dostoevsky and the other giant of late 19th century

Dostoevsky has also been noted as having expressed anti-Semitic sentiments. In the recent biography by Joseph Frank, "The Mantle of the Prophet," Frank spent much time on "A Writer's Diary" - a regular column which Dostoevsky wrote in the periodical "The Citizen" from 1873 to the year before his death in 1881. Frank notes that the Diary is "filled with politics, literary criticism, and pan-Slav diatribes about the virtues of the Russian Empire, [and] represents a major challenge to the Dostoevsky fan, not least on account of its frequent expressions of anti-Semitism." ["Dostoevsky's leap of faith This volume concludes a magnificent biography which is also a cultural history." Orlando Figes. SUNDAY TELEGRAPH (LONDON). Pg. 13. September 29, 2002.] Frank, in his foreword that he wrote for the book "Dostoevsky and the Jews", attempts to place Dostoevsky as a product of his time. Frank notes that Dostoevsky "did" make anti-semitic remarks, but that Dostoevsky's writing and stance by and large was one where Dostoevsky held a great deal of guilt for his comments and positions that were anti-semitic. [Dostoevsky and the Jews (University of Texas Press Slavic series) (Hardcover) 2 Joseph Frank, "Foreword" pg. xiv. by David I. Goldstein ISBN-10: 0292715285] Steven Cassedy, for example, alleges in his book, "Dostoevsky's Religion", that much of the points made that depict Dostoevsky’s views as an anti-Semite, do so by denying that Dostoevsky expressed support for the equal rights of and for the Russian Jewish population, a position that was not widely supported in Russia at the time.cite book |title= Dostoevsky's Religion |last= Cassedy |first= Steven |authorlink= |coauthors= |year= 2005 |publisher= Dostoevsky and Existentialism With the publication of " Novels * " hort stories * "Mr. Prokharchin" (1846) Non-fiction * "Winter Notes on Summer Impressions" (1863) ee also * References External links * [http://www.FyodorDostoevsky.com FyodorDostoevsky.com] - The definitive Dostoevsky fan site: discussion forum, essays, e-texts, photos, biography, quotes, and links. Persondata Источник: Fyodor Dostoevsky

* "" (Двойник. Петербургская поэма ) (1846)

* "Netochka Nezvanova" (Неточка Незванова) (1849)

* "

* "

* "The House of the Dead" (Записки из мертвого дома) (1862)

* "

* "

* "The Gambler" (Игрок) (1867)

* "The Idiot" (Идиот) (1869)

* "

* "The Possessed" (Бесы) (1872)

* "

* "

* "Novel in Nine Letters" (1847)

* "Polzunkov" (1847)

* "The Landlady" (1847)

* "The Jealous Husband" (1848)

* "White Nights" ("Белые ночи") (1848)

* "

* "

* "

* "

* "

* The Uncle's Dream (1859)

* "

* "The Crocodile" (1865)

* "Bobok" (1873)

* "

* "The Heavanly Christmas Tree" (1876)

* "

* "

* "

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* Voluntarism

*

*

* [http://www.kevinrkosar.com/conference-journal-aut-1998.pdf Article on Notes from the Underground] "Love and the Underground Man," Conference Journal, Aut. 1998.

* [http://www.fedordostoievsky.com/ingles/ingles1.htm FedorDostoievsky.com] - Dostoevsky fan site

* [http://Dostoyevsky.thefreelibrary.com/ Fyodor Dostoevsky's brief biography and works]

*

* [http://digital.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/search?author=Dostoyevsky%2c+ Selected Dostoevsky e-texts from Penn Librarys digital library project]

* [http://www.asiaing.com/the-gospel-in-dostoyevsky-selections-from-his-works.html The Gospel in Dostoyevsky: Selections from His Works]

* [http://librivox.org/notes-from-the-underground-by-fyodor-dostoyevsky/ Free audiobook] of "

* [http://ilibrary.ru/author/dostoevski/ Full texts of some Dostoevsky's works in the original Russian]

* [http://www.magister.msk.ru/library/dostoevs/ Another site with full texts of Dostoevsky's works in Russian]

* [http://www.fmdostoyevsky.com Fyodor Dostoyevsky] - Biography, ebooks, quotations, and other resources

* "Crime and Punishment," Fyodor Dostoevsky, translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. Vintage Classics, 1992, New York.

* "Crime and Punishment," Fyodor Dostoevsky, translated by Constance Garnett, introduction by Joseph Frank. Bantam Books, 1987, New York.

* [http://www.kiosek.com/dostoevsky/contents.html Dostoevsky Research Station]

* [http://people.emich.edu/wmoss/publications/ ALEXANDER II AND HIS TIMES: A Narrative History of Russia in the Age of Alexander II, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky]

* "Dostoevsky," Joseph Frank. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1979-2003 (5 volumes).

*

* [http://www.the-ledge.com/flash/ledge.php?book=75&lan=UK Dostoyevsky 'Bookweb' on literary website The Ledge, with suggestions for further reading.]

* [http://fyodordostoevskychronicle.blogspot.com Fyodor Dostoevsky Chronicle] by Erik Lindgren

* [http://www.helium.com/tm/437407/fyodor-mikhailovich-dostoyevsky-before Fyodor Dostoevsky Biography] by Iolo Savill

*worldcat id|id=lccn-n79-29930

* [http://www.mootnotes.com/literature/dostoevsky/index.html Dostoevsky works (HTML/PDF), media gallery & interactive timeline]

NAME= Dostoevsky, Fyodor Mikhailovich

ALTERNATIVE NAMES= Dostoyevsky, Fyodor Mikhailovich; Фёдор Миха́йлович Достое́вский (Russian)

SHORT DESCRIPTION= Russian novelist

DATE OF BIRTH= birth date|1821|11|11|mf=y

PLACE OF BIRTH= Moscow

DATE OF DEATH= death date|1881|2|9|mf=y

PLACE OF DEATH= Saint Petersburg

Patricia Highsmith

| Patricia Highsmith | |

|---|---|

Publicity photo from 1966 |

|

| Born | Mary Patricia Plangman January 19, 1921 Fort Worth, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | February 4, 1995 (aged 74) Locarno, Switzerland |

| Occupation | novelist |

| Nationality | American |

| Period | 1950 onward |

| Genres | suspense, psychological thriller, crime fiction |

| Literary movement | modernist literature |

| Notable work(s) | Strangers on a Train, The Ripliad |

|

Influences

|

|

|

|

|

| Signature | |

|

wwnorton.com/catalog/featured/highsmith/welcome.htm |

|

Patricia Highsmith (January 19, 1921 – February 4, 1995) was an American novelist and short-story writer most widely known for her psychological thrillers, which led to more than two dozen film adaptations. Her first novel, Strangers on a Train, has been adapted for stage and screen numerous times, notably by Alfred Hitchcock in 1951. In addition to her acclaimed series about murderer Tom Ripley, she wrote many short stories, often macabre, satirical or tinged with black humor. Although she wrote specifically in the genre of crime fiction, her books have been lauded by various writers and critics as being artistic and thoughtful enough to rival mainstream literature. Michael Dirda observed, "Europeans honored her as a psychological novelist, part of an existentialist tradition represented by her own favorite writers, in particular Dostoevsky, Conrad, Kafka, Gide, and Camus."[1]

Contents |

Early life

Highsmith was born Mary Patricia Plangman in Fort Worth, Texas, the only child of artists Jay Bernard Plangman (1889—1975) and his wife, the former Mary Coates (September 13, 1895 — March 12, 1991); the couple divorced ten days before their daughter's birth.[2] She was born in her maternal grandmother's boarding house. In 1927, Highsmith, her mother and her adoptive stepfather, artist Stanley Highsmith (whom her mother had married in 1924), moved to New York City.[2] When she was 12 years old, she was taken to Fort Worth and lived with her grandmother for a year. She called this the "saddest year" of her life and felt abandoned by her mother. She returned to New York to continue living with her mother and stepfather, primarily in Manhattan, but she also lived in Astoria, Queens. Pat Highsmith had an intense, complicated relationship with her mother and largely resented her stepfather. According to Highsmith, her mother once told her that she had tried to abort her by drinking turpentine, although a biography of Highsmith indicates Jay Plangman tried to persuade his wife to have an abortion, but she refused.[3] Highsmith never resolved this love–hate relationship, which haunted her for the rest of her life, and which she fictionalized in her short story "The Terrapin", about a young boy who stabs his mother to death. Highsmith's mother predeceased her by only four years, dying at the age of 95.

Highsmith's grandmother taught her to read at an early age, and Highsmith made good use of her grandmother's extensive library. At the age of eight, she discovered Karl Menninger's The Human Mind and was fascinated by the case studies of patients afflicted with mental disorders such as pyromania and schizophrenia.

Comic books

In 1942, Highsmith graduated from Barnard College, where she had studied English composition, playwriting and the short story. Living in New York City and Mexico between 1942 and 1948, she wrote for comic book publishers. Answering an ad for "reporter/rewrite", she arrived at the office of comic book publisher Ned Pines and landed a job working in a bullpen with four artists and three other writers. Initially scripting two comic book stories a day for $55-a-week paychecks, she soon realized she could make more money by writing freelance for comics, a situation which enabled her to find time to work on her own short stories and also live for a period in Mexico. The comic book scriptwriter job was the only long-term job she ever held.[2]

With Nedor/Standard/Pines (1942–43), she wrote Sgt. Bill King stories and contributed to Black Terror. For Real Fact, Real Heroes and True Comics, she wrote comic book profiles of Einstein, Galileo, Barney Ross, Edward Rickenbacker, Oliver Cromwell, Sir Isaac Newton, David Livingstone and others. In 1943–45, she wrote for Fawcett Publications, scripting for such Fawcett Comics characters as the Golden Arrow, Spy Smasher, Captain Midnight, Crisco and Jasper. She wrote for Western Comics in 1945–47.

When she wrote The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955), one of the title character's first scam victims is comic book artist Frederick Reddington, a parting gesture directed at the earlier career she had abandoned: "Tom had a hunch about Reddington. He was a comic-book artist. He probably didn't know whether he was coming or going."[4]

Novels and adaptations

Highsmith's first novel was Strangers on a Train, which emerged in 1950, and which contained the violence that became her trademark.[5] At Truman Capote's suggestion, she rewrote the novel at the Yaddo writer's colony in Saratoga Springs, New York.[6] The book proved modestly successful when it was published in 1950. However, Hitchcock's 1951 film adaptation of the novel propelled Highsmith's career and reputation. Soon she became known as a writer of ironic, disturbing psychological mysteries highlighted by stark, startling prose.

Highsmith's second novel, The Price of Salt, was published under the pseudonym Claire Morgan. It garnered wide attention as a lesbian novel because of its rare happy ending.[5] She did not publicly associate herself with this book until late in her life, probably because she had extensively mined her personal life for the book's content.[2]

As her other novels were issued, moviemakers adapted them for screenplays: The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955), Ripley's Game (1974) and Edith's Diary (1977) all became films.

She was a lifelong diarist, and developed her writing style as a child, writing entries in which she fantasized that her neighbors had psychological problems and murderous personalities behind their façades of normality, a theme she would explore extensively in her novels.

Major themes in her novels

Highsmith included homosexual undertones in many of her novels and addressed the theme directly in The Price of Salt and the posthumously published Small g: a Summer Idyll. The former novel is known for its happy ending, the first of its kind in lesbian fiction. Published in 1952 under the pseudonym Claire Morgan, it sold almost a million copies. The inspiration for the book's main character, Carol, was a woman Highsmith saw in Bloomingdale's department store, where she worked at the time. Highsmith acquired her address from the credit card details, and on two occasions after the book was written (in June 1950 and January 1951) spied on the woman without the latter's knowledge.

The protagonists in many of Highsmith's novels are either morally compromised by circumstance or actively flouting the law. Many of her antiheroes, often emotionally unstable young men, commit murder in fits of passion, or simply to extricate themselves from a bad situation. They are just as likely to escape justice as to receive it. The works of Franz Kafka and Fyodor Dostoevsky played a significant part in her own novels.

Her recurring character Tom Ripley—an amoral, sexually ambiguous con artist and occasional murderer—was featured in a total of five novels, popularly known as the Ripliad, written between 1955 and 1991. He was introduced in The Talented Mr. Ripley.[7] After a 9 January 1956 TV adaptation on Studio One, it was filmed by René Clément as Plein Soleil (1960, aka Purple Noon and Blazing Sun) with Alain Delon, whom Highsmith praised as the ideal Ripley. The novel was adapted under its original title in the 1999 film directed by Anthony Minghella, starring Matt Damon, Gwyneth Paltrow, Jude Law and Cate Blanchett.

A later Ripley novel, Ripley's Game, was filmed by Wim Wenders as The American Friend (1977). Under its original title, it was filmed again in 2002, directed by Liliana Cavani with John Malkovich in the title role. Ripley Under Ground (2005), starring Barry Pepper as Ripley, was shown at the 2005 AFI Film Festival but has not had a general release.

In 2009, BBC Radio 4 adapted all five Ripley books with Ian Hart as Ripley.

Personal life

According to her biography, Beautiful Shadow, Highsmith's personal life was a troubled one; she was an alcoholic who never had a relationship that lasted for more than a few years, and she was seen by some of her contemporaries and acquaintances as misanthropic and cruel. She famously preferred the company of animals to that of people and once said, "My imagination functions much better when I don't have to speak to people."

"She was a mean, hard, cruel, unlovable, unloving person", said acquaintance Otto Penzler. "I could never penetrate how any human being could be that relentlessly ugly."[8]

Other friends and acquaintances were less caustic in their criticism, however; Gary Fisketjon, who published her later novels through Knopf, said that "she was rough, very difficult... but she was also plainspoken, dryly funny, and great fun to be around."[8]

Highsmith had relationships with women and men, but never married or had children. In 1943, she had an affair with the artist Allela Cornell (who committed suicide in 1946 by drinking nitric acid[9]) and in 1949, she became close to novelist Marc Brandel. Between 1959 and 1961 she had a relationship with Marijane Meaker, who wrote under the pseudonyms of Vin Packer and Ann Aldrich, but later wrote young adult fiction with the name M.E. Kerr. Meaker wrote of their affair in her memoir, Highsmith: A Romance of the 1950s.

In the late 1980s, after 27 years of separation, Highsmith began sharing correspondence with Meaker again, and one day she showed up on her doorstep, slightly drunk and ranting bitterly. Meaker once recalled in an interview the horror she felt upon noticing the changes in Highsmith's personality by that point.[10]

"Highsmith was never comfortable with blacks, and she was outspokenly anti-semitic—so much so that when she was living in Switzerland in the 1980s, she invented nearly 40 aliases, identities she used in writing to various government bodies and newspapers, deploring the state of Israel and the 'influence' of the Jews".[11] Nevertheless, some of her best friends were Jewish, such as author Arthur Koestler, and admired Jewish writers such as Franz Kafka and Saul Bellow. She was accused of misogyny because of her satirical collection of short stories Little Tales of Misogyny.

Highsmith loved woodworking tools and made several pieces of furniture. She kept pet snails; she worked without stopping. In later life she became stooped, with an osteoporotic hump.[2] Though her writing—22 novels and eight books of short stories—was highly acclaimed, especially outside of the United States, Highsmith preferred for her personal life to remain private. She had friendships and correspondences with several writers, and was also greatly inspired by art and the animal kingdom.

Highsmith believed in American democratic ideals and in the promise of US history, but she was also highly critical of the reality of the country's 20th century culture and foreign policy. Tales of Natural and Unnatural Catastrophes, her 1987 anthology of short stories, was notoriously anti-American, and she often cast her homeland in a deeply unflattering light. Beginning in 1963, she resided exclusively in Europe. In 1978, she was head of the jury at the 28th Berlin International Film Festival.[12]

Death

Highsmith died of aplastic anemia and cancer in Locarno, Switzerland, aged 74. She retained her United States citizenship, despite the tax penalties, of which she complained bitterly, from living for many years in France and Switzerland. She was cremated at the cemetery in Bellinzona, and a memorial service conducted at the Catholic church in Tegna, Switzerland.[3]

In gratitude to the place which helped inspire her writing career, she left her estate, worth an estimated $3 million, to the Yaddo colony.[5] Her last novel, Small g: a Summer Idyll, was published posthumously a month later.

Bibliography

Novels

- Strangers on a Train (1950)

- The Price of Salt (as Claire Morgan) (1952), also published as Carol

- The Blunderer (1954)

- The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955)

- Deep Water (1957)

- A Game for the Living (1958)

- This Sweet Sickness (1960)

- The Cry of the Owl (1962)

- The Two Faces of January (1964)

- The Glass Cell (1964)

- A Suspension of Mercy (1965), also published as The Story-Teller

- Those Who Walk Away (1967)

- The Tremor of Forgery (1969)

- Ripley Under Ground (1970)

- A Dog's Ransom (1972)

- Ripley's Game (1974)

- Edith's Diary (1977)

- The Boy Who Followed Ripley (1980)

- People Who Knock on the Door (1983)

- Found in the Street (1987)

- Ripley Under Water (1991)

- Small g: a Summer Idyll (1995)

Short-story collections

- Eleven (1970; also known as The Snail-Watcher and Other Stories)

- Little Tales of Misogyny (1974)

- The Animal Lover's Book of Beastly Murder (1975)

- Slowly, Slowly in the Wind (1979)

- The Black House (1981)

- Mermaids on the Golf Course (1985)

- Tales of Natural and Unnatural Catastrophes (1987)

- Nothing That Meets the Eye: The Uncollected Stories (2002; posthumously published)

Collected works

- Patricia Highsmith: Selected Novels and Short Stories (W.W. Norton, 2010)

Miscellaneous

- Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction (1966)

- Miranda the Panda Is on the Veranda (1958; children's book of verse and drawings, co-written with Doris Sanders)

Awards

- 1946 : O. Henry Award for best publication of first story, for "The Heroine" in Harper's Bazaar

- 1951 : Edgar Award nominee for best first novel, for Strangers on a Train

- 1956 : Edgar Award nominee for best novel, for The Talented Mr. Ripley

- 1957 : Grand Prix de Littérature Policière, for The Talented Mr. Ripley

- 1963 : Edgar Award nominee for best short story, for "The Terrapin"

- 1964 : Dagger Award – Category Best Foreign Novel, for The Two Faces of January from the Crime Writers' Association of Great Britain

- 1975 : Grand Prix de l'Humour Noir for L'Amateur d'escargot

- 1990 : Chevalier dans l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from the French Ministry of Culture

See also

References

- ^ "This Woman Is Dangerous" The New York Review of Books. July 2, 2009. Accessed November 15, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Joan Schenkar, "The Misfit and Her Muses", Wall Street Journal, December 8, 2009, p. A19

- ^ a b The Talented Miss Highsmith: The Secret Life and Serious Art of Patricia Highsmith, by Joan Schenkar, 2009; ISBN# 978-0-312-30375-4

- ^ Highsmith, Patricia. The Talented Mr. Ripley, Vintage Crime/Black Lizard, 1992.

- ^ a b c Patricia Cohen, "The Haunts of Miss Highsmith", New York Times, December 10, 2009.

- ^ Yaddo Writers: June 1926 – December 2007.

- ^ Coward-McCann, 1955

- ^ a b Mystery Girl | The Talented Mr. Ripley | Biz | News | Entertainment Weekly

- ^ Wilson, A. Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith. Bloomsbury, London. 2004

- ^ De Bertodano, Helena (June 16, 2003). "A passion that turned to poison". The Daily Telegraph (London). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/donotmigrate/3596749/A-passion-that-turned-to-poison.html.

- ^ Winterson, Jeanette (December 20, 2009). "Patricia Highsmith, Hiding in Plain Sight". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/20/books/review/Winterson-t.html?ref=review.

- ^ "Berlinale 1978: Juries". berlinale.de. http://www.berlinale.de/en/archiv/jahresarchive/1978/04_jury_1978/04_Jury_1978.html. Retrieved 2010-08-04.

External links

- Works by or about Patricia Highsmith in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Patricia Highsmith Papers at the Swiss Literary Archives

- BBC Four audio interviews with Highsmith

- This Woman Is Dangerous Michael Dirda on Highsmith and her work from The New York Review of Books

- Patricia Highsmith at the Internet Movie Database

- The Haunts of Miss Highsmith – New York Times – Books

- Hiding in Plain Sight – New York Times Sunday Review of "THE TALENTED MISS HIGHSMITH -The Secret Life and Serious Art of Patricia Highsmith" By Joan Schenkar.

- 1987 RealAudio interview with Patricia Highsmith by Don Swaim (MP3 also available)

|

|||||

- 1921 births

- 1995 deaths

- People from Fort Worth, Texas

- Barnard College alumni

- American comics writers

- American crime fiction writers

- American horror writers

- American novelists

- American short story writers

- Members of the Detection Club

- Bisexual writers

- Golden Age comics creators

- Deaths from anemia

- LGBT comics creators

- LGBT writers from the United States

- Female comics writers

- Cancer deaths in Switzerland

Источник: Patricia Highsmith

Другие книги схожей тематики:

| Автор | Книга | Описание | Год | Цена | Тип книги |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fyodor Dostoevsky, Patricia Highsmith | Fyodor Dostoevsky. Crime and Punishment. Patricia Highsmith. Ripley's Game (комплект из 2 книг) | — Vintage, Vintage Classics Подробнее... | 2007 | 789 | бумажная книга |

См. также в других словарях:

Patricia Highsmith — Nombre completo Patricia Highsmith Nacimiento 19 de enero de 1921 Fort Worth, Texas … Wikipedia Español

Patricia Highsmith — Publicity photo from 1966 Born Mary Patricia Plangman January 19, 1921(1921 01 19) Fort Worth, Texas, U.S. Died February 4, 1995 … Wikipedia

Ahmet Ümit — (1960 en Gaziantep) es un escritor turco. Ha publicado varias novelas de crimen, así como poesía, numerosos relatos cortos y cuentos de hadas. También escribió ensayos sobre Franz Kafka, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Patricia Highsmith y Edgar Allan… … Wikipedia Español

List of fiction works made into feature films — The title of the work is followed by the work s author, the title of the film, and the year of the film. If a film has an alternate title based on geographical distribution, the title listed will be that of the widest distribution area. Books 0… … Wikipedia

Erast Fandorin — Infobox character colour = Red name = Erast Petrovich Fandorin caption = Oleg Menshikov as Erast Fandorin in the 2005 movie The State Counsellor first = The Winter Queen last = cause = nickname = Funduk ( schoolmates ); Erasmus ( Count Zurov )… … Wikipedia

List of fictional anti-heroes — This list is for characters in fictional works who exemplify the qualities of an anti hero. Characteristics in protagonists that merit such a label can include, but are not limited to:*imperfections that separate them from typically heroic… … Wikipedia